TIMO FAHLER & DANIEL GIBSON

TODO FINE

26 October 2019 to 30 November 2019

TIMO FAHLER & DANIEL GIBSON

TODO FINE

TWO PERSON EXHIBITION (PROJECT ROOM & MAIN GALERY)

EXHIBITION DATES: 26 OCTOBER 2019 to 30 NOVEMBER 2019

OPENING RECEPTION: SAT, OCT 26 FROM 6:00 - 9:00 PM

GALLERY HOURS: TUES - SAT / 1PM - 6PM

NEW IMAGE ART, 7920 SANTA MONICA BLVD LOS ANGELES CA 90046

Todo fine is Spanglish for “everything is fine.” When asked, Timo Fahler and Daniel Gibson say that not everything is fine. It never was and will never be. But here we are. Todo fine then also means everything is not fine. While certain parts of our world collapse––democracy, the environment, a sense of community–– others parts are built––awareness, social (infra)structures, a new sense of community. The exhibition is an attempt at being open to everything; the things we want to see and hear and those we do not.

The spatial sequencing of Todo Fine follows Gibson and Fahler through the conception of their relationship to their current practice. The back room of the exhibition, deprived of color, references the artists’ past and returns to their time spent at their San Diego artist-run space in 2000. This was before they established their art practice, while both were developing a reliance on various substances. Less than to relive this time period and elevate its circumstances, the artists chose to return to this moment as it marks the beginning of their artistic careers as well as their friendship which culminates here in this duo exhibition at New Image Art.

In the back room, Fahler’s sculptures, partial self-portraits, appear as frozen, dreamlike memories built from only plaster and rebar. you’re a pickle now, you can never be a cucumber again poses a figure showering in a cheap standing sink who washes himself with a soap bar inlaid with Love Roses (known as crackpipes but disguised as a gift for your lover). Although cast from life, identity is obfuscated in Fahler’s sculptures. Lying face down, a light urgently pulsates along with the slow, loud heartbeat of the sleeping figure in speedball-flush (this train does not stop). Portraying normal human actions, showering and sleeping, the pipes and the throbbing heartbeat hint at the complex coexistence of addiction, the awareness of its consequences, and the inability to break the cycle that sustains it. Fahler’s sculptures are flanked by three of Gibson’s black and white paintings. In passing through, a giant butterfly occupies the majority of the painting and the space within it. Below the butterfly, a figure lies in a bed looking up to this manifestation that carries its own symbolic narrative. Many of Gibson’s paintings contain symbolism; often imagery associated with the desert around the US-Mexico border––hidden figures, eyes watching, or plants and animals specific to the area. For Gibson, this painting recalls the sound of migrants opening the outdoor faucet to drink water at night below his childhood bedroom window. From the perspective of a first generation Mexican-American, the story of a child listening to migrants drink water is also the story of migrants crossing the border. They are a part of each other.

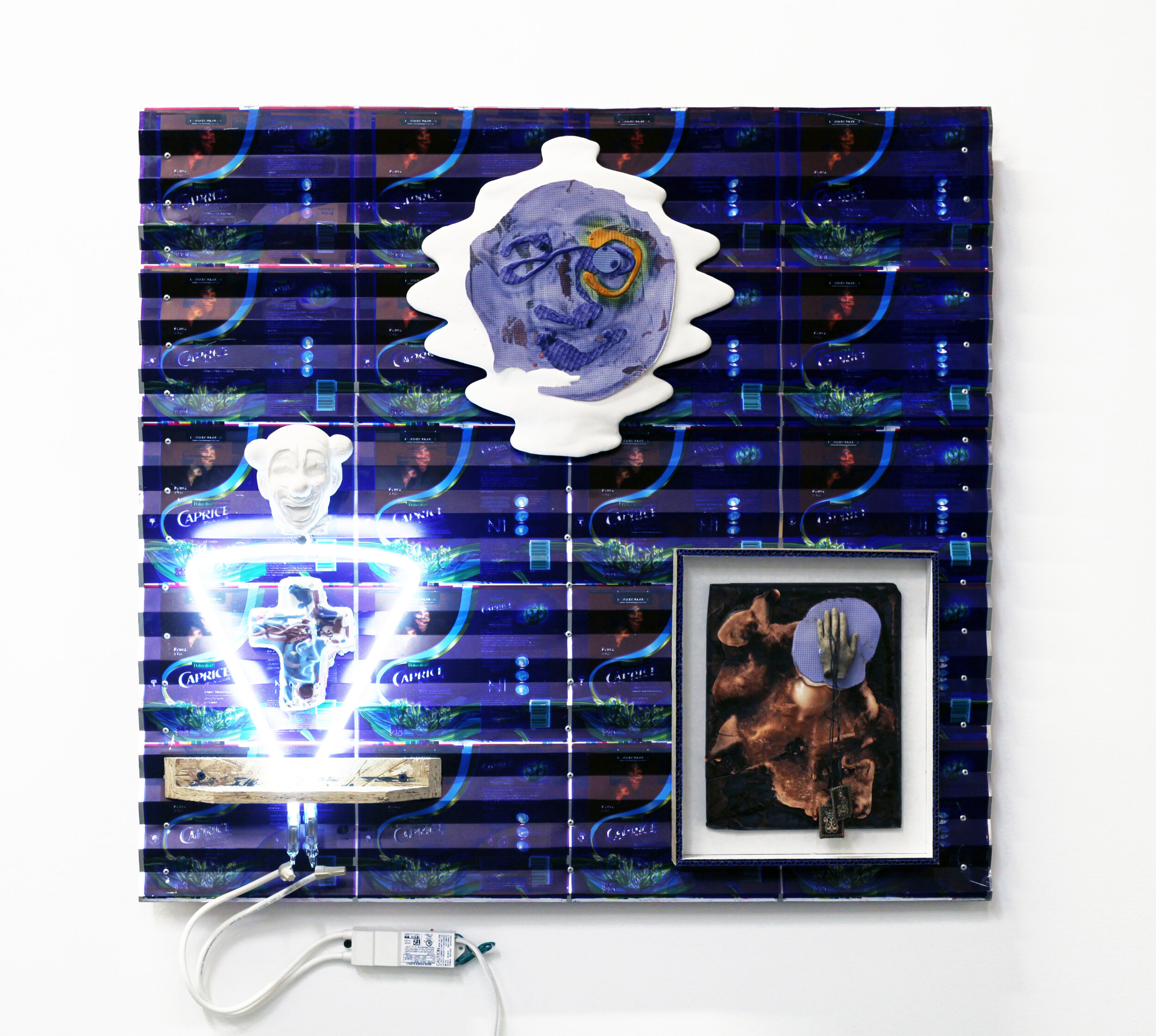

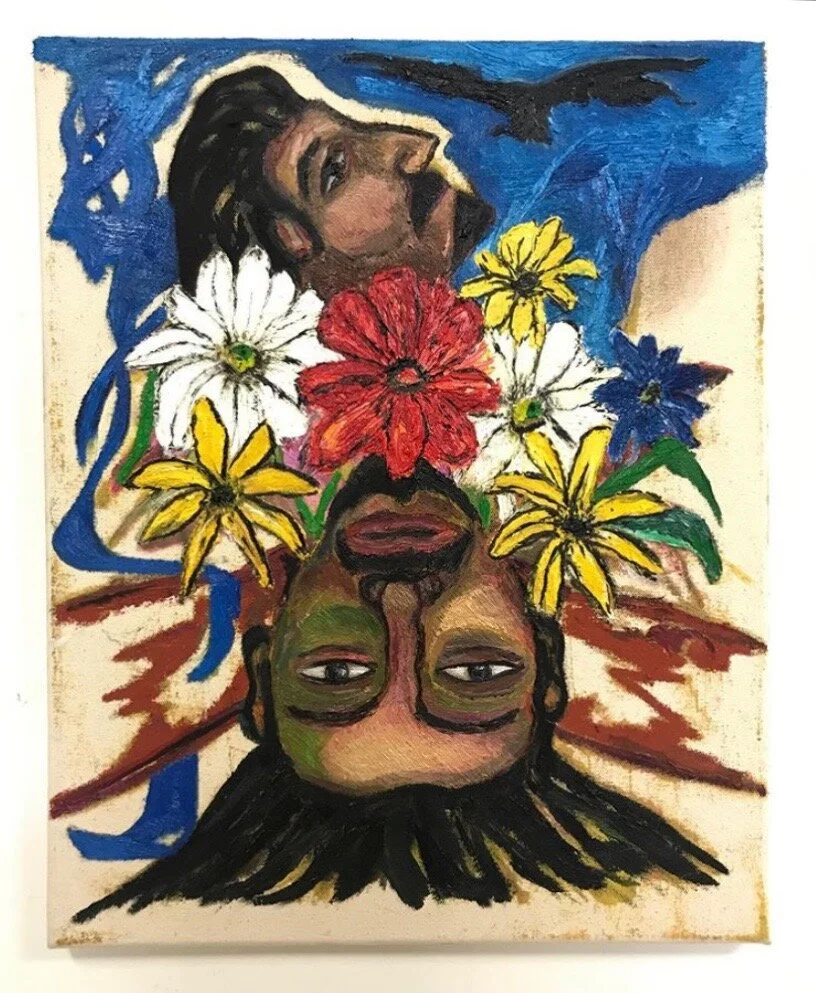

Migration, identity and change are themes that surface in the work of both artists, whose families crossed the border earlier in the previous century, and become more prominent in the works in the front room. In Gibson’s paintings we see a family atop a train hiding as it rides through the night, or figures wading through a field of flowers hardly recognizable as they begin to resemble their surroundings. The sun and the moon alternate positions in his work, guiding and hiding the people that Gibson depicts, and illuminating their existence to the viewer to which these lives and journeys remain largely invisible. Fahler’s work in the front room, although more abstract, refers to familial histories of both his paternal and maternal sides and coalesces Mexican and German heritage into his understanding and experience of American identity. Utilitarian materials and mercado paraphernalia are used to create objects, such as Classical columns, framed paintings or pedestals, reminiscent of but in contrast to their Western archetypes. Fahler’s work here reverses hierarchies and opens up room for a reinterpretation of what American can mean.

Rooted in subjective pasts and moving into larger societal conversations, the works in Todo Fine, rather than solely criticizing current affairs, consider the role of contradicting perspectives and how within opposition room for change might unveil itself.

-Text by Laura Macarena