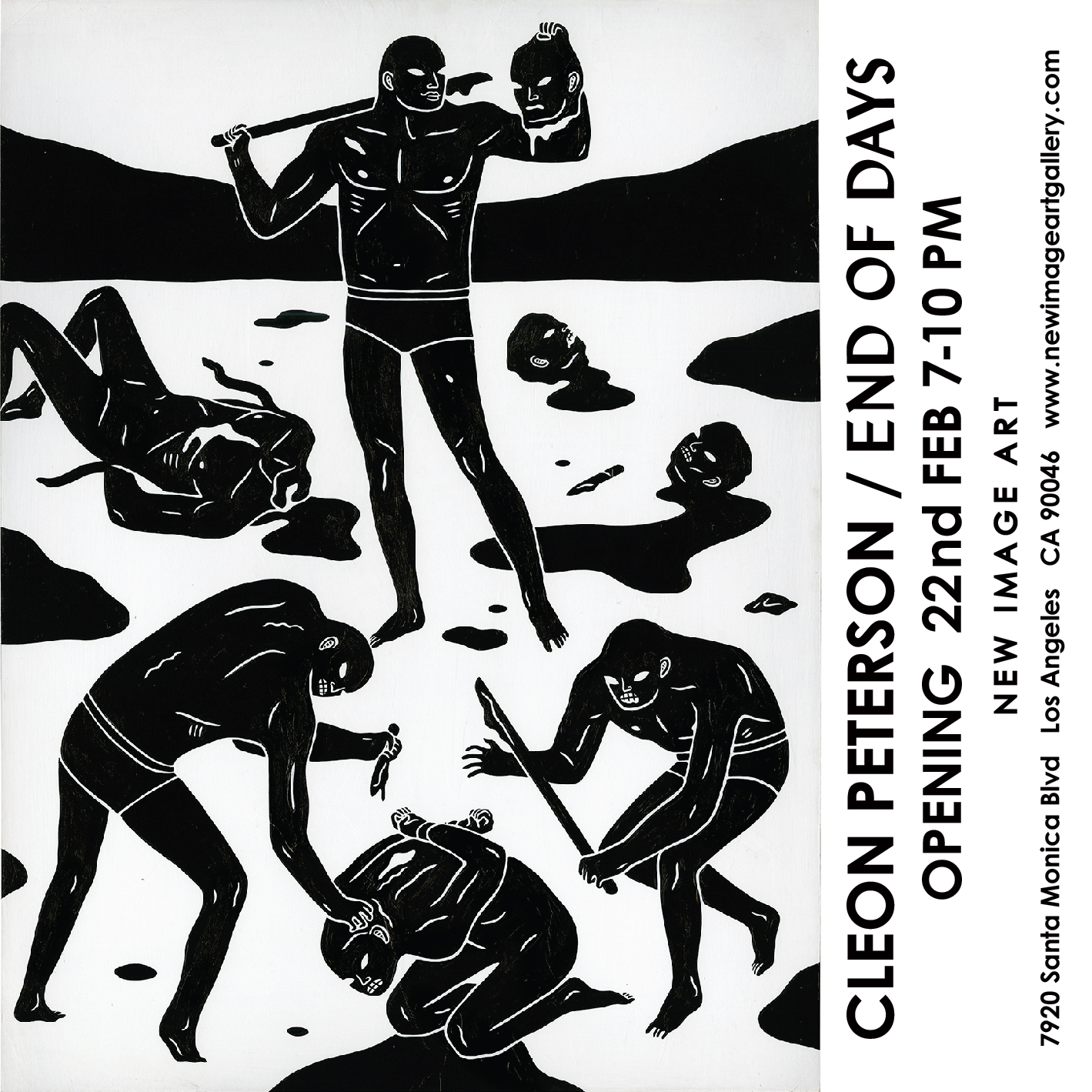

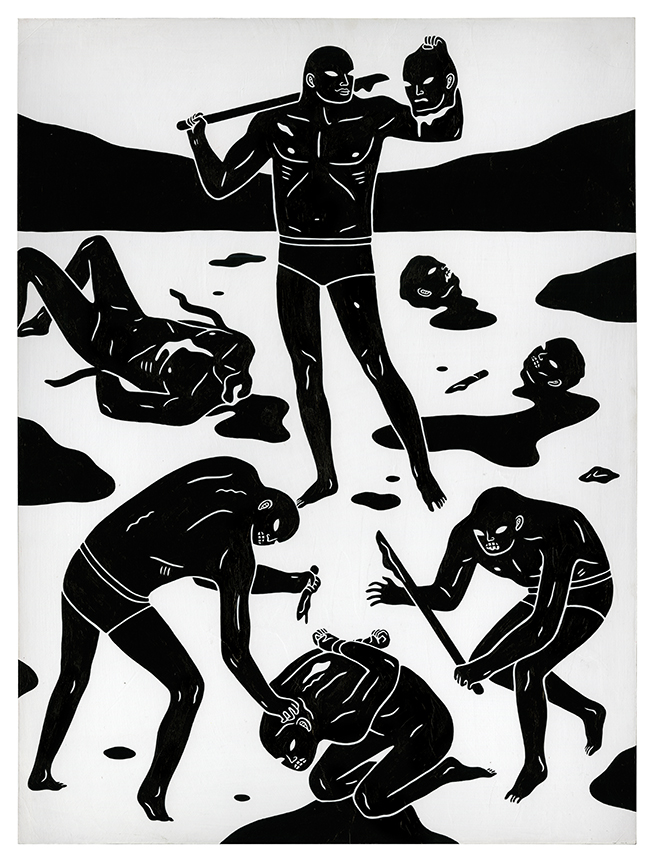

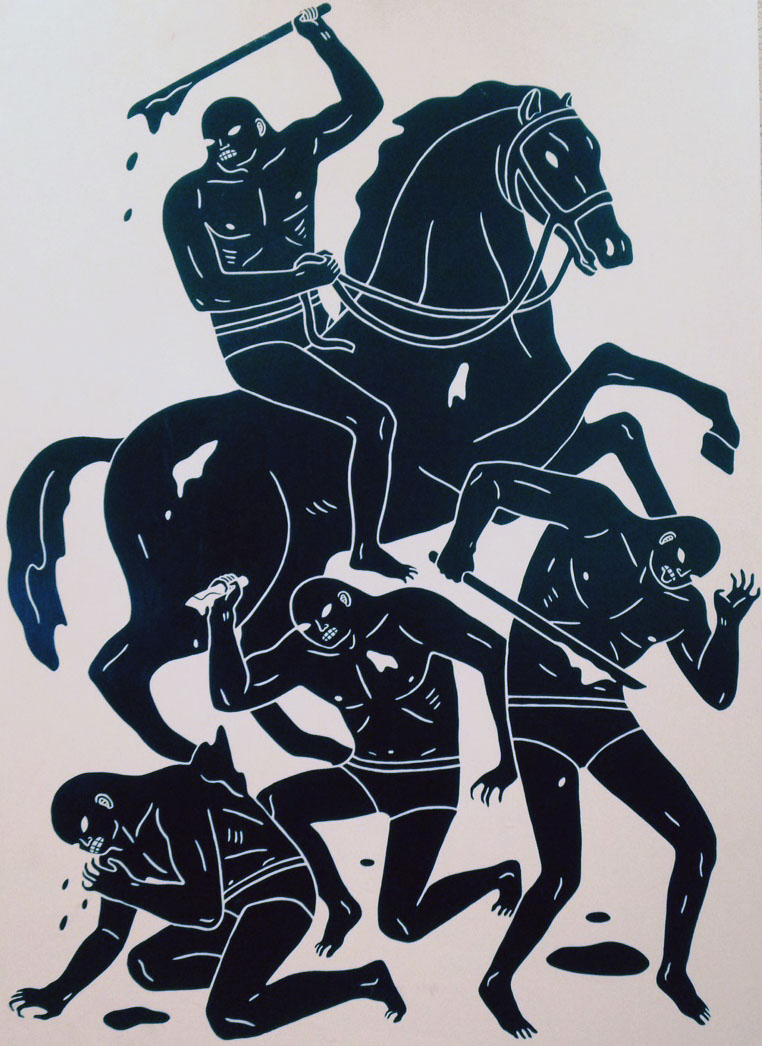

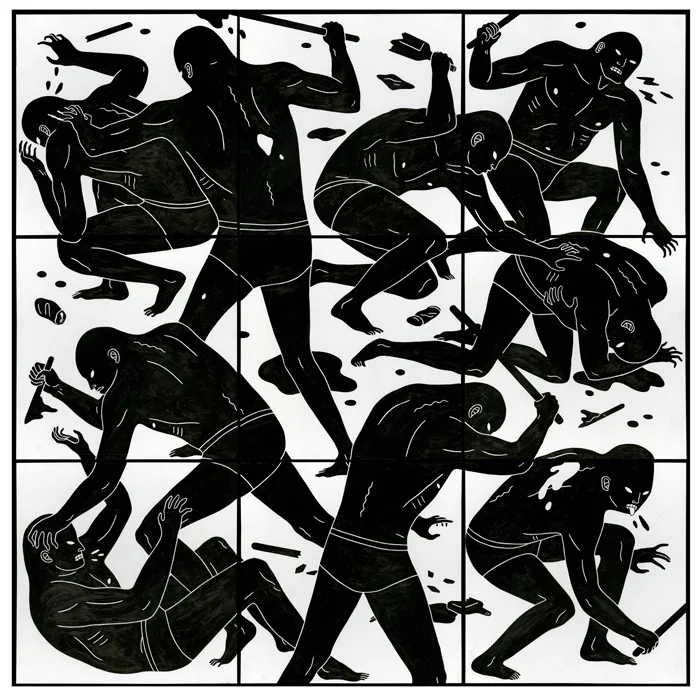

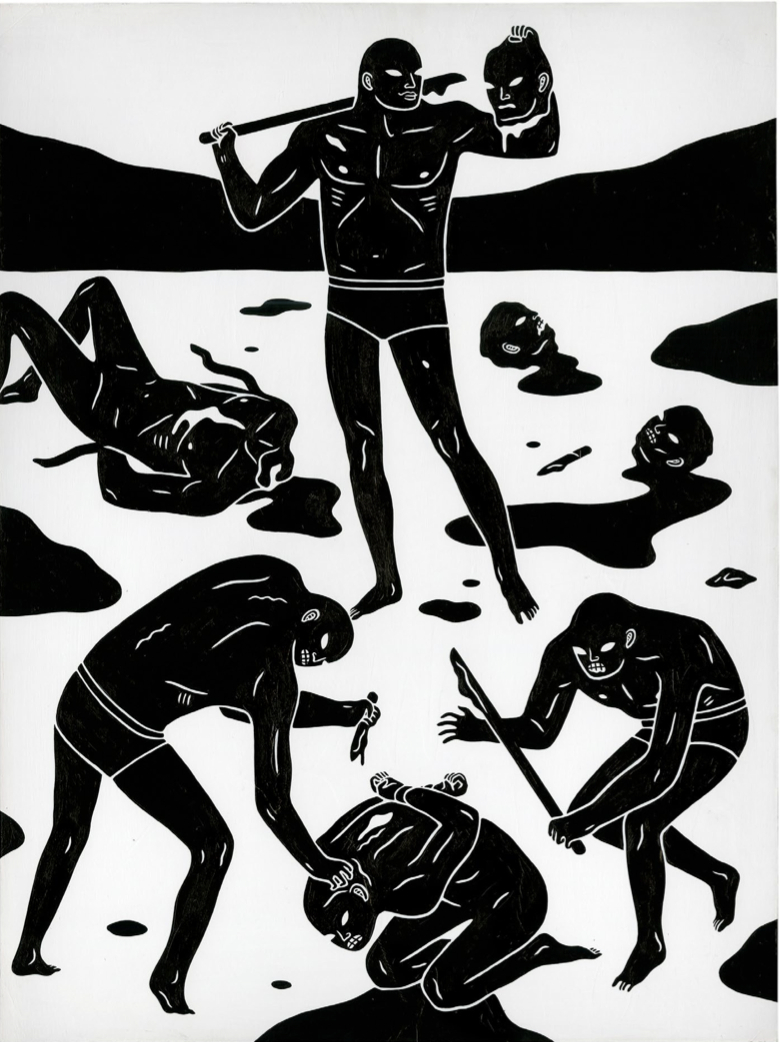

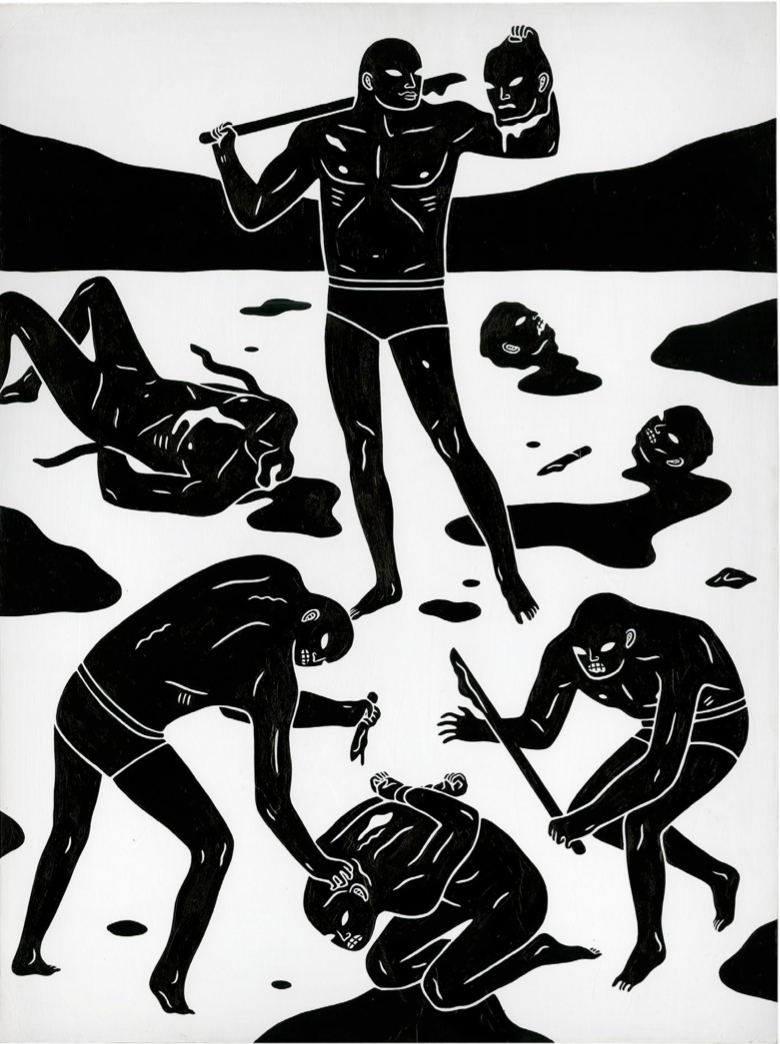

In Cleon Peterson’s End of Days, opening February 22nd at New Image Art, Peterson’s world of depravity does not simply crash and burn: it reverses polarity, inherited not by the meek but by the vengeful and merciless. Whatever days have ended, they have been succeeded by a new age of barbarism, with clear winners and losers. The triumphant take no trophies, apart from the occasional severed head, but the defeated have clearly lost more than their viscera – they have lost all semblance of control, dignity, strength and, most of all, hope.

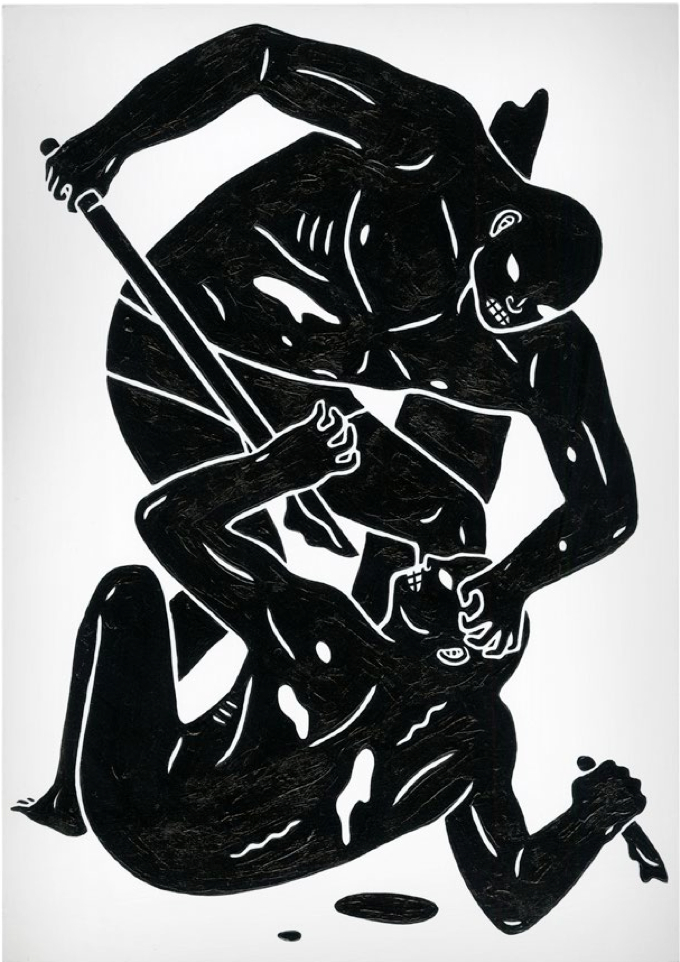

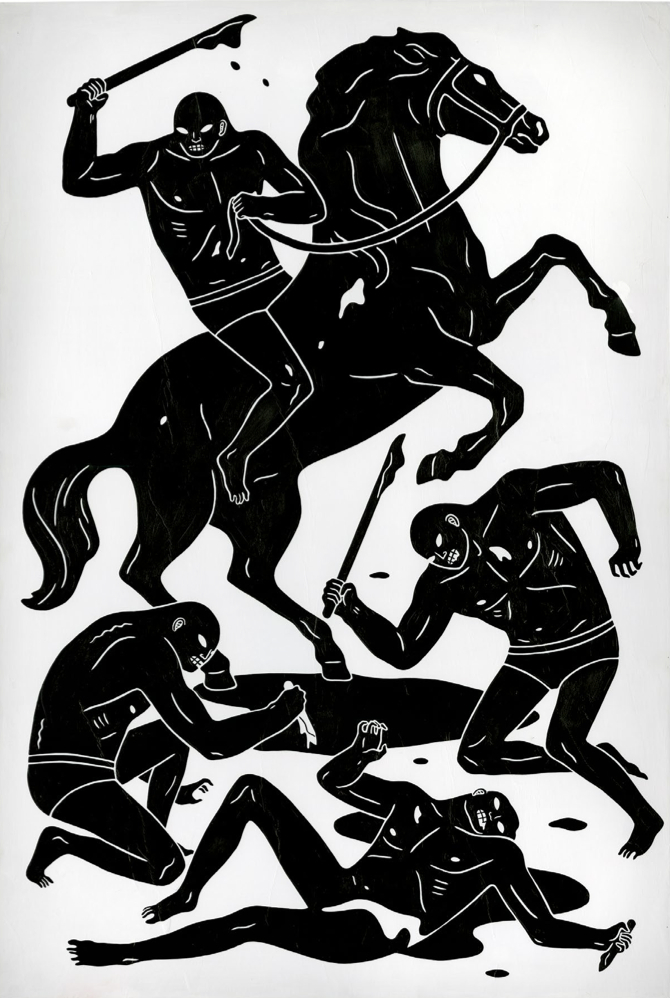

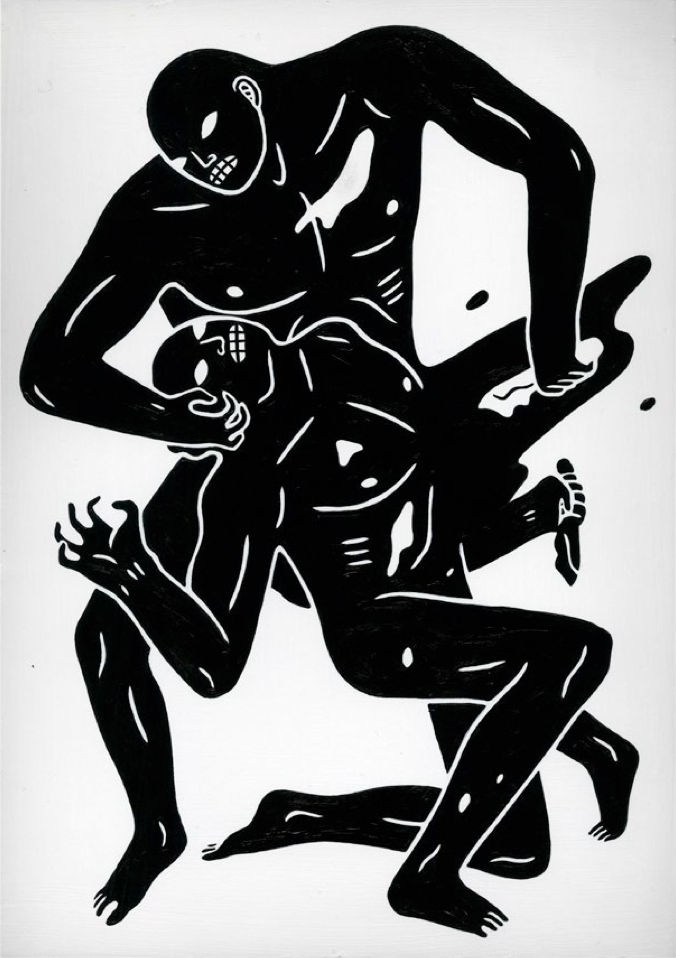

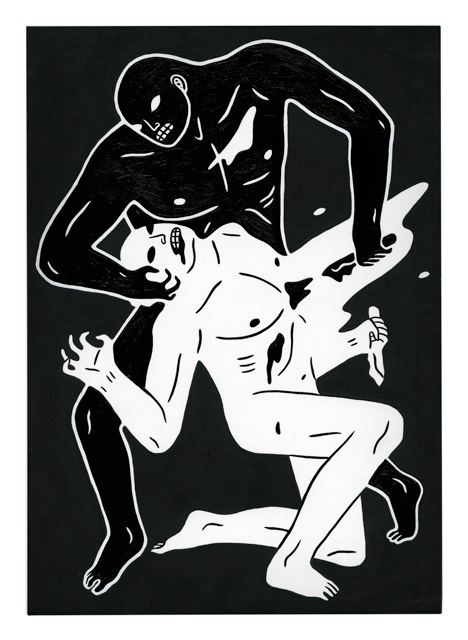

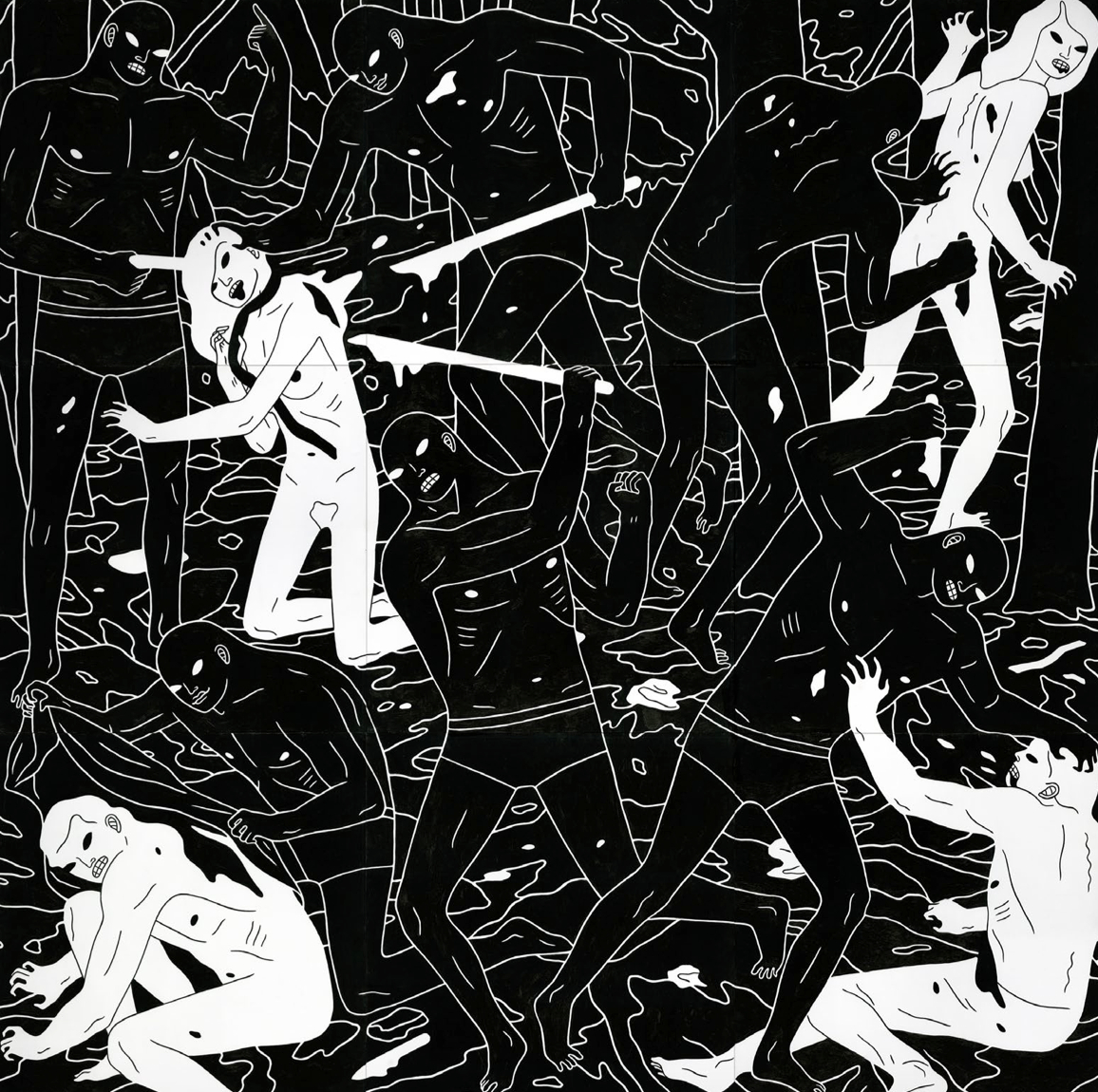

But not all is lost, nor is it over. If that sounds like the good news, well, it’s not. The scenes of brutality are depicted in medias res, after the first blows were struck, in most cases not quite lethally. As the victims live to suffer, their tormenters seem to revel in that persistence. In fact, the tormenters, which Peterson calls the “shadows,” appear to derive their strength from their subversion. Over the years that he has depicted the shadows in his work, Peterson has often cited their genesis in the writings of Jung and Nietzsche, both of whom described the tension between the parts of the self that the psyche expresses and those it represses. In Newtonian fashion, the force of repression is met with an equal force of reprisal. In End of Days, then, the viewer is left to question what precipitating crimes could merit such grisly punishment.

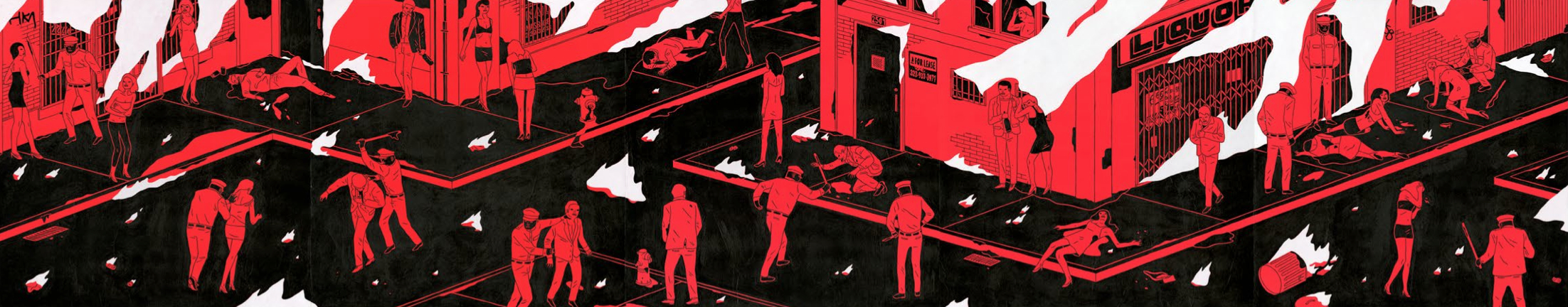

Whereas the backdrop for the shadows is a neutral netherworld, other images in End of Days are set amid urban calamity. In these, the shadows are replaced with uniformed “enforcers” – a more orderly sort of violence for a more carefully constructed world. The two settings are equally nightmarish, though, and in their horror lies a grim revelation of the most essential quality of fear: powerlessness. What we are left with is a sublimation of paranoia, bypassing struggle on the arc from anxiety straight into torment.